Experimental experiences

Radio Here

Radio Here started with a simple question: What do you think someone should hear?

People all over the world submitted sounds that made them happy, or angry, made them feel safe, or scared.

These sounds are broadcast on a series of low‑powered, hand-built FM transmitters. The broadcast soundscape becomes a public listening space, an environment that encourages visitors to discover what someone thought they should hear. It is an environment that encourages exploration, but above all, it creates a space to listen.

This was my thesis project for my MFA in Design.

Photographs by Mark Roudebush

Creating a community listening place.

We are told that we are more connected to one another than at any other point in history. The Internet has made it possible to reach far points of the world instantly. It has promised to democratize communication, to give everyone who can participate an equal voice and equal access to information.

The Internet has made it possible to reach far points of the world instantly. It has promised to democratize communication, to give everyone who can participate an equal voice and equal access to information.

This promise has not been fulfilled.

There are a multitude of complex interrelated reasons why these digital tools have not created the promised utopia. Deregulation, privatization, and commercialization are just a few of the contributing factors to this wicked problem. At a surface level, a visit to the general comments section of any news story, forum, or entertainment site quickly reveals a huge problem. The communications relationship model of sender and receiver is broken. Everyone wants to be a sender without taking time to be a receiver. In other words, if everyone is talking then no one is listening.

Radio Here is a space for listening. This project takes the participatory actions of communication—namely: sending and receiving—and separates them in time and location. Participants are invited to share their own sounds during the sending phase, through an open call for submissions. Visitors to Radio Here are invited to discover these submitted sounds during the receiving phase, using hand-held radio receivers to explore an environment built of low-powered FM transmissions. As a one-directional medium, radio encourages participants to explore a space completely built on this act of receiving—on the experience of listening. In the final phase of the participatory cycle, visitors may respond to or share what they have heard.

This project attempts to become what Marshal McLuhan has called an “anti‑environment” (McLuhan). By creating a space that challenges the expected conventions of technological participation, the “anti-environment” might reveal the current state of the existing environment. My project creates a space for asynchronous participation—a place where sending and receiving, speaking and listening, are spatially separated.

“Let’s start with your own familiar space. Change in a tiny space could resonate to larger space but without microscopic change no radical change would be possible.”

Photograph by Thomas Mai0rana

Welcome to Radio Here

RADIO HERE started with a simple question: What do you think someone should hear?

People all over the world submitted sounds that made them happy, or angry, made them feel safe, or scared.

These sounds are broadcast on a series of low‑powered, hand-built FM transmitters. The broadcast soundscape becomes a public listening space, an environment that encourages visitors to discover what someone thought they should hear. It is an environment that encourages exploration, but above all, it creates a space to listen.

With Radio Here I build upon theoretical foundations to explore the overlap and interplay between the architectural, the invisible, and the participatory. I approach this overlap using terrestrial radio as my medium, leveraging what radio is (radiogéine) and what radio does (create a space for community) as my parameters. I am designing an open public space—a permeable space that includes rather than excludes.

More specifically, this space is constructed and defined by an invisible architecture of sound, achieved by using extremely low-powered FM transmitters that are all broadcasting on the same frequency. Using a receiver tuned to this frequency, a participant may explore this audio landscape. Traveling beyond the limit of the signal strength reveals the hidden edges of this environment. It is impossible to hear everything at once, and as listeners pick up and lose parts of the transmissions, their experience becomes physically situated. Listeners choose their own path through the audio environment, which questions the nature of performance and participation, and of individual and collective experience. As a one-directional medium, the use of radio encourages participants to explore a space completely built on receiving—on the experience of listening. This is intended to create an active space, as “it is possible to listen without necessarily listening to anything. Listening can therefore be understood as being in a state of anticipation, of listening out for something.” (Lacey 7) This experience of listening while experiencing Radio Here is intended to create a sense of searching, exploration, and a desire to hear.

This project creates an experience that takes apart the Shannon–Weaver model of communication, which loosely comprises of a sender, channel (the medium carrying the sender’s message), and a receiver. (Shannon and Weaver) By creating three distinct modes for participation, Radio Here encourages participants to engage with each piece of the communication model as a point of focus.

Mode I: Sending

Submitting sounds to Radio Here

My first task for Radio Here was deciding how to facilitate participation in the most open and simple way possible. While we are now used to photographing almost every aspect of our lives, most people are not used to thinking about capturing sound. Any barrier would discourage people from participating. I also did not want to exclude those who do not have access to a smart phone. It was important for me to not let technology become a participatory condition.

Sound submissions for Radio Here are conceived as being captured in one of two ways:

A: Using a smart phone to capture field recordings

Field recordings may be made using voice notes or another sound capture app on a smart phone. For these recordings, participants can choose to upload their sounds to a public Google Drive folder via the Radio Here website, or email it to the Radio Here email address.

B: Using any phone to leave a voice-mail

For those who want to phone in, or do not have access to a smart phone, three Google Voice numbers are set up to collect recordings. This mode of participation is only able to capture those who wish to describe a sound, or read something. Because Google Voice is a voice over IP equivalent, transmissions are heavily compressed in order to efficiently transmit data packets. This has the effect of canceling any sounds other than the voice.

Have you heard?

Getting the word out about Radio Here.

A series of posters provided specific listening prompts.

Radio Here is built around the answers to a simple question: “What do you think someone should hear?” However simple it may seem, this is a very broad question, and can be intimidatingly hard to answer. Therefore, it is broken down into categorical prompts:

Record the sound of something that

... makes you angry.

... makes you happy.

... makes you feel safe.

... makes you scared.

... you think someone should hear.

Posters for Radio Here each announce one of the five prompts under the broader heading of “What do you think someone should hear?” Each poster has a row of tear-off strips with the web address for the Radio Here project website (visitradiohere.com), and one of three Google voice phone numbers.

Radio Here business cards were helpful during one-on-one conversations.

I also created a set of cards to hand out while having conversations with people face-to-face. On the cards I used the broader prompt “What do you think someone should hear?” and included both the project web address as well as an email address for submitting sounds directly.

Both the posters and the cards were intended to get people to visit the project website.

The Radio Here website became a hub of activity for the “receiving” portion of the project. It is a single page containing a call to action with the submission categories, a short description of the project, and a section for “frequently asked questions.”

Following the submission prompt links send visitors to one of three Google Drive folders where they can leave a description of their sound and upload it. The numbers of the associated Google Voice phone numbers are also listed. With the intent of the project being centered around what people wanted others to hear, I did not want to add my interpretation or judgment to sounds submitted to each prompt.

The Radio Here website is a call to action, intended to made it easy to upload field recordings or call one of the thematically related Google Voice numbers.

Mode II: Receiving

Listening to Radio Here

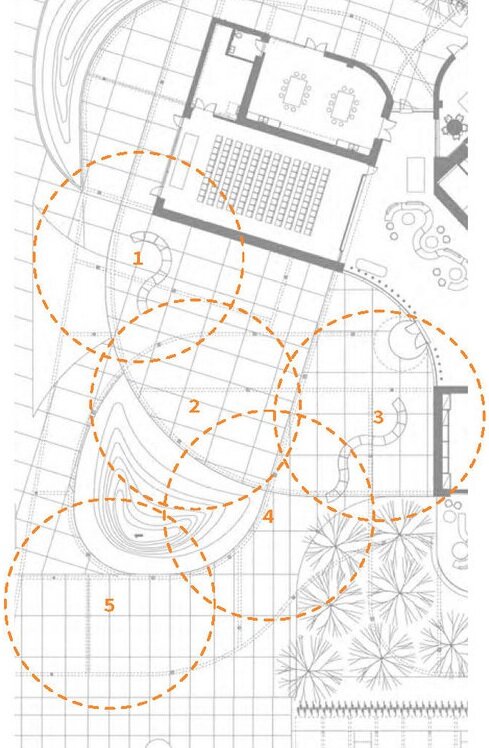

Ultimately, Radio Here is a project about listening. Content collected during the first mode of participation is broadcast through a series of ultra-low-powered FM transmitters. In the first installation, these transmitters were positioned under the Grand Canopy outside of the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art. Using hand-held and battery-powered FM receivers, visitors to the site had the opportunity to seek out these transmissions. As participants exploring an audio-only environment, they are encouraged to actively listen and discover sounds. This became my invisible architectural space.

The Radio Here transmitters were placed under the grand canopy at the Manetti Shrem Museum of Art.

The Radio Here radio stations.

The radio stations used two circuits in order to broadcast the collected sounds. The first circuit was a simple MP3 board that played the sounds from a memory card on a continuous loop. The output from the MP3 circuit was wired to the transmitter circuit. These were hand-built using Tetsuo Kogawa’s “simplest transmitter” schematic. I chose to work with this transmitter because of the limited range of the broadcast strength—approximately 30 feet.

Each transmitter was tuned to broadcast on the same FM frequency. This allowed visitors to move between each station physically rather than using the tuning dial on the hand-held receivers. Visitors to Radio Here picked up, crossed, and dropped signals as they explored the audio landscape.

The radio stations are small enough to hold in the palm of your hand.

Transmitter prototype and finished model.

Mode III: Sending (again)

Reflecting on the experience of visiting Radio Here

At the end of their visit to Radio Here, visitors may pick up a postcard. This is another mode of participation, and another way that visitors might share a sound with someone else. It is my hope that visitors, and those they connect with by sending a postcard, begin listening.

The Radio Here ecosystem.

Why Radio?

Research for this project has led me down many paths of inquiry. Aside from the theoretical research that will be covered in the next section, there are texts that situated my work thematically. As Radio Here utilizes radio transmissions to create its listening space, I needed to steep myself in the thinking and theory surrounding the long history of radio and broadcasting. I explored sources discussing the very early days of radio history; from the culture of amateur HAM radio operators prior to World War I, to the “Golden Age” of broadcast radio in the United States during the inter-war years—a time when corporate media interests fought governmental takeover by proving their civic ambitions for radio (Goodman). The history of the low-power FM (LPFM) movement in the United States was of particular interest. The relatively recent LPFM movement that began in the early 1990s has its roots in the corporate media claim to having a civic ambition for radio. Arguments in favor of LPFM licensing hinge on calls for free speech and are anti-corporate, and anti-consolidation. Media conglomerates argue that scale creates a diversity of voices, but they are in fact creating less diversity in practice. Through my research, I began to understand the fight over access to the airwaves as one closely related to community development and environmental justice theories. I argue for radio space as a community space, and as a place where communities gather. This argument is further supported through a conception of radio as an inherently local medium. Radio Here attempts to disrupt the idea of radio as a far-reaching broadcast medium by focusing on an ultra-local application.

Two broad directions emerged from my explorations of radio focused around what radio is and what radio does. Philosophers and theorists began contemplating the impact of radio almost as soon as it was introduced in the 1920s. The playwright and director Berthold Brecht and the philosopher and broadcaster Walter Benjamin both wrote about the recently introduced medium in Weimar Germany from 1926 to 1933. Both quickly identified the flaw in radio’s one-sided directionality, and Benjamin desired a radio that was a voice of the community, “a radio that turns the listener from a passive consumer into an active producer, expanding the public’s understanding of its own expertise.” (Benjamin and Rosenthal xxv)

Emerging from this early thinking around what radio is, came the concept of radiogénie or, radiogenics. Film was emerging as an art form simultaneously, and the more familiar idea of photogenics can be thought of as the visual form of radiogenics. However, photogenics originally covered more conceptual ground than “looking good in front of the camera.” It explored the essence of filmic vision as it related to time and the way in which film reveals what was previously un-seeable. For radio, radiogenic forms of broadcasting sought to discover the essence of this new medium. “Dissatisfied with radio as a peddlar of second-rate ersatz culture, critics called for new forms that were properly radio, that exploited those properties that made radio distinct from what had gone before.” (Lacey 93)

What are the unique qualities of radio? The radiogenic debates and discussions revolved around the disembodied voice, the separate and widespread audience, and the need to fill 24-hours of programming. Having the ability to be “always on” framed debates about recorded and reproduced sound (the machine playing machine sounds) versus the “live” nature of radio (once you heard something over the air, you couldn’t hear it again).

Thinking about what radio is, the radiogenic was primarily concerned about forms of content and how that content was and could be delivered in a way unique to radio. Today, a distinction needs to be made amongst streaming and internet radio, satellite and digital radio, and terrestrial radio. These formats share the word “radio” and problematize radiogenic thinking, repositioning the debate about what makes radio, radio. Radio Here engages specifically with the ideas and technologies inherent to terrestrial radio. This project considers the properties of radio that are physically defined by transmitter power and shaped by the landscape. Radio is fundamentally a local media defined by the conditions of the environment it is situated in. With this view of what radio is, I think about the ways in which it becomes a community builder and meeting place. I believe that this is what radio does.

A Short History of Radio Policy and the Low-Power FM Movement As It Relates to Community Development Theory

With the 1934 Communications Act, the United States Congress established the Federal Communications Committee. The newly formed FCC was a governmental agency responsible for the regulation of radio—seen as the first technologically mediated mass media. The FCC’s early years hinged around the enforcement of the pre-existing 1927 Radio Act. This act required members of the National Association of Broadcasters to broadcast in the “public interest, convenience, or necessity.” This vague task of protecting the “public interest” created debate and political battles over use and access to the airwaves that continue to this day. Corporate interests, non-profits, religious groups, political organizations, special interests, and “pirates” are all fighting for increasingly limited allocations of the radio spectrum. Each group has a different view of how to define and broadcast in the “public interest.”

The United States began licensing commercial broadcasting in the AM band in 1920. As with most new technologies, access was limited at first to large national corporations with capital and resources beyond those of most community groups. Over the next 10 years, these companies established themselves as media powerhouses, protecting their territory in the radio spectrum with financial and political might. When FM radio was invented in the 1930s, there was little commercial interest in the new frequencies. Because few existing radios at the time could reach that portion of the spectrum, there were smaller audiences to advertise to. However, this created a political opportunity for the FCC to allot a portion of the spectrum to non-commercial stations. To encourage stations with limited funding to get established and on the air, a low-power license was created that relaxed the minimum transmitter power requirements. These expanded regulations made access to the airwaves cost effective for organizations with limited funding and no advertising revenue. Small community stations were localized alternatives to the commercial corporate entities broadcasting at a nation-wide scale on the AM dial. By the end of the 1960s the typical types of low-power stations were college and university stations, locally owned community stations, or non-locally owned community stations.

By 1978 FM radio had grown in popularity, proving the market viability of the newer portion of the radio dial. Corporate pressure moved the FCC to adopt new rules ending the low-power license and forcing small community-run stations to close. These stations were quickly replaced with corporate and non-local entities. The response to this governmentally sanctioned corporate takeover of the FM spectrum was pirate radio. Thus began the era of “media activism” concerning local radio and advocacy for low-power FM. While a far cry from the corporate interpretation and practice of “public interest” radio of the 1930s, media activists were renewing that public spirit in a whole new political environment.

Andy Opel examines the history of the low-power FM (LPFM) movement through the lens of New Social Movement Theory. He cites Alberto Melucci as its primary theorist, and outlines the major theoretical characteristics of New Social Movements: the desire to create cultural codes as opposed to fighting for resources, having a planet-wide perspective, building communities versus protesting, and as recognizing global and social interconnectedness. Melucci identifies these movements as having discreet goals instead of a desire for a complete “revolution” and as giving participants the ability to create their identities through participation. (in Opel 17–18)

Within Melucci’s theoretical framework, Opel situates the core issues in the struggle for legitimizing LPFM and for providing legal protection against corporate domination. The applied lens of New Social Movement Theory highlights the importance of radio as a community-defining space. The proponents of LPFM, in part, framed their case for revised license designations through a refined definition of “public interest.” To legitimize the LPFM movement, the activists took it upon themselves to define the “public interest” on their own terms. This changed the public discourse to reflect their definition in defense against larger corporate domination. Most importantly, it turned the LPFM movement into a community.

Defining “community” becomes an essential part of discussing “community radio,” and this is something that the low-power FM community did. Because of the strong discourse for community amongst proponents of LPFM and the earliest “pirates,” these broadcasters became community organizers. Through the shows they produced and put on air they demonstrated that large corporate entities were not acting in the interest of their local and specific community needs. Community voices were not included in corporate media, and were explicitly excluded from representation. In this way, the fight for LPFM became an organizational and community development tool—the voice and representative of each localized community. Therefore, in addition to creating community, “local” becomes a natural extension of the LPFM movement.

Opel shows through his research that the LPFM advocates were able to create a narrative that defined the communities occupying radio. When Congress passed the Radio Broadcasting Preservation Act of 2000—the act that included the LPFM licensing—the advocates’ voices were reflected in the legislation. Low-power FM was created and defined by the communities that demanded it, and the advocates were able to create a locally defined public space within the radio spectrum.

The technological mediation of community is still a topic of discussion and debate today. A recent New York Times Magazine article explored the concept of community in the digital era.

“The psychologists David W. McMillan and David M. Chavis ... cited an important distinction between two types of community that have long coexisted. One is geographical—neighborhood, town, city—and the other is “relational,” concerned with the interconnections among people. Our sense of community seems to shift steadily among these very different modes of thinking. Over the decades, its meaning has lost the precision of city limits and has expanded to accommodate groups with shared values, planned and intentional organizations and a general sense of interpersonal connectedness. In 2018, it feels as if community is about being recognized as a certain kind of person—when it’s not merely about fitting into a broad category. In other words, our sense of community is less and less about being from someplace and more about being like someone.” (Chocano)

Although this New York Times piece is taking a critical look at the supposed community development taking place through “new media,” the discussion also become a defense for community radio. I believe that it is over the airways that these relational and geographic communities overlap.

Despite its seeming ubiquity, radio is fundamentally a local infrastructure with a finite range of coverage. Antenna heights, power levels, and topography all contribute to the physical limitations of the dissemination of radio waves. In this way, all radio is local radio. What appears disconnected is actually physically situated and defined by the landscape. Being in range or out of range creates conditions shared with architecture, those of being inside or outside.

The Environmental Justice of Community Radio

As a place where communities gather, radio space should be considered a space to be protected. Theories of environmental justice have been primarily applied to “brown” environmental cases involving pollution, land toxicity, or the placement of heavy industry in relation to poor or under-served neighborhoods. “Brown” environmental justice concerns itself with places that directly relate to physical health risks. More recent research has expanded the field of environmental justice to encompass “green” applications such as parks, community gardens, and open space that relate to mental health. This new environmental justice movement expands the definition of environment as the places where people live, work, learn, and play. (Anguelovski)

I believe that this new theory of environmental justice might be expanded further still to encompass the “invisible” environment of radio. Community radio specifically can be viewed as a space that should be protected as an important spatial justice arena. In the United States, free radio advocates liken the airwaves to the National Parks System. The radio spectrum is owned by the public and is regulated by the Federal Communications Commission, who acts as the “park rangers” of the radio dial. Commercial broadcasters are licensed to utilize space on the spectrum, but do not own the frequency they are broadcasting on. Free radio advocates are simply fighting for public access to this public resource. They believe that

“free radio stations are one of the few avenues available for community members to freely express their grievances against the governing and owning classes. In modern America, the town hall meeting is obsolete, and where town hall meetings do occur, they are most often used to drum up support for unpopular policies or stalled reelection campaigns. In contrast, free radio stations allow community members to publicly and even anonymously express their grievances, unencumbered by the daunting presence of political leaders and police.” (Soley 47)

The view of radio space as a replacement for the town hall highlights this case for an “airwaves” version of environmental justice. The very physical meeting space that is the town hall is paralleled by the new gathering space provided by community radio. “In new environmental spaces, participants are removed from the daily stresses they suffer, they can express themselves freely without the control of dominant groups, and they receive support to confront difficult situations and grow through the experience.” (Anguelovski 170) I believe that community radio becomes this new environmental space where the community represents and expresses its own needs. The community learns to address relevant issues, host the dialogue pertinent to those issues, and develop locally appropriate responses.

This view of the community reflecting its own community needs through community radio can be seen in the locally specific programming of KDRT, a 99-watt community radio station in Davis, California. The “Davis Garden Show” is a call-in gardening advice show pertinent to the local climate and conditions, “Davisville” presents stories about the unique people and events around town, and “Independent and Local” plays music from local independent and unsigned bands. These shows are just a few examples of the ways that KDRT is creating a space for local concerns and interests. “If residents feel that they are able to intervene themselves on a space and lead projects in which they have to decide how to achieve this balance between environmental sustainability and memory, they might feel less uprooted from the space.” (Anguelovski 172) While these shows might appear quaint to a listener from a bigger city, these shows define and connect residents to the space they share. KDRT shares this belief through its organizational value on “Localism:”

“We are connected by histories, places, and stories that make up our community—Yolo County and beyond. Sharing local experiences connects us to each other and to our place. KDRT promotes interaction, connections, and a sense of belonging among residents. When people tell stories and others listen, they create community.” (Our Values | KDRT 95.7FM Davis)

Thinking about expanding environmental justice into the realm of community radio becomes relevant when we think about it as another space being occupied by the community. “Media space” and the “media environment” are important places of gathering, discussion, and definition for a community. Therefore, control of this space should fall to the community and not to national commercial stations that do not reflect the specific nuances of the location where a community lives, works, learns,

and plays.

Considering radio as an architectural space and building an audio environment

In addition to studies related to radio and LPFM history, I have been interested in architectural studies that conceive of the abstract and non-material as formal structures and habitable environments. This thinking has a rich tradition in the work of radical architecture groups of the 1960s such as Archigram and Superstudio. In particular, I found the work of Cedric Price to be most influential in this line of thinking. Price had a conception of time in architecture, and he thought about how to build spaces that only exists when needed. As exemplified by his unbuilt project The Fun Palace, he conceived of structures that met the needs of the people who used them, and did not live past the desire for those structures to exist. Furthermore, he envisioned a role for architecture as a means of support, rather than suppression:

“What do we have architecture for? It’s a way of imposing order on establishing a belief, and that is the course of religion to some extent. Architecture doesn’t need those roles anymore; it doesn’t need imperialism; it’s too slow, it’s too heavy and, anyhow, I as an architect don’t want to be involved in creating law and order through fear and misery. Creating a continuous dialogue with each other is very interesting; it might be the only reason for architecture...” (Price 57)

It is my hope that the architectural environment of Radio Here meets these requirements, becoming a space where communities gather to grow and have an ongoing conversation.

Practical Review

Radio Here attempts to contribute to the lineage of sound-based investigations. The many works produced in this field have been expressed as art, technical achievements, theoretical imaginings, and political challenges. Drawing on many of these ideas, Radio Here has been especially inspired to take the work of Pauline Oliveros, Christina Kubisch, Tetsuo Kogawa, the sound-collective Ultra-red, and the “Montreal Sound Map” project as points of departure. Through their work, these artists and thinkers helped me re-imagine the acts of hearing and listening, and how these acts define a tangible sense of place.

Pauline Oliveros

composer, performer, and humanitarian

The late Pauline Oliveros was a composer, performer, and founder of the Deep Listening Institute. Through her musical work and teachings, she elevated the act of listening. Oliveros understood listening as an “active” mode of participation, not a passive one—and thought about listening as a way to be completely present in the moment. This sense of action gave listening the potential to be a political act. She believed that “listening is directing attention to what is heard, gathering meaning, interpreting and deciding on action.” (O’Brien) It is surprising to me that in all my reading on listening, political or otherwise, her name was never mentioned.

Of particular interest for my project was her book Deep Listening: a composer’s sound practice. In it, Oliveros collects the prompts and instructions she had created for her own deep listening practice as well as those used for teaching classes and workshops. The descriptively titled “Listening Questions” is a list of 40 simple questions aimed to stimulate more purposeful and active listening. A few examples from this list: “2. When do you notice your breath?” “13. When do you feel sound in your body?” and “40. What sound would you like whispered in your ear?” (Oliveros)

Discovering Pauline Oliveros’ work, writing, and philosophy gave me the courage and theoretical foundation to elevate the active practice of listening as a valid design outcome for Radio Here.

Christina Kubisch

visual artist, musician, and composer

Christina Kubisch is a Berlin-based visual artist, musician, and composer who works primarily with sound. Since the late 1970s, Kubisch has been exploring electromagnetic fields first through installation pieces and, beginning in 2004, through “Electrical Walks.” These walks make audible the typically inaudible electro-magnetic fields that persist in public space; sounds emitted by smart parking meters and security gates in stores. Kubisch makes a new type of urban exploration possible, expanding the experience of public space to include what is normally hidden from our senses. “The perception of everyday reality changes when one listens to the electromagnetic fields; what is accustomed appears in a different context. Nothing looks the way it sounds. And nothing sounds the way it looks.” (Kubisch, Electrical Walks)

I first encountered Christina Kubisch’s work at the SFMOMA as part of the show Soundtracks that ran from July 2017 to January 2018. She had two pieces on display, Cloud (2011/2017) and Electrical Walks San Francisco. I was inspired by how she conceived of the visitor interactions with her sound spaces.

“The basic idea of these sound spaces is to provide the viewer/listener access to his own individual spaces of time and motion. The musical sequences can be experienced in ever-new variations through the listener’s motion. The visitor becomes a ‘mixer’ who can put his piece together individually and determine the time frame for himself.” (Kubisch, Electromagnetic Induction)

As listening environments, both Cloud (2011/2017) and Electrical Walks San Francisco focuses on the exploration of space to discover sounds. I like this active listening aspect to Kubisch’s work. Radio Here strives for this same spirit of seeking. However, Radio Here is not focused on revealing hidden sounds, and instead asks for participation in finding sounds that will be shared with others to discover in the listening space.

Tetsuo Kogawa

performance artist, philosopher, and media critic

Japanese artist Tetsuo Kogawa’s explores “micro radio.” In his manifesto for radio art, he envisions micro radio as a hyper-local response to the globalization of media whether broadcast via radio waves or digitally. “Given the age of various global means such as the satellite communications and the Internet, micro radio can concentrate itself into its more authentic territory: microscopic airwave space.” (Kogawa)

Tetsuo Kogawa designs simple, extremely low-powered FM transmitters. He aims to make access to the local airwaves technically accessible. Kogawa is in opposition to most designers who are interested in extending the reach of their broadcasts. For him, lower-powered transmissions that force locality are a key concept and feature of micro radio.

“Why don’t you go to a radio station just as you did to theatres. Micro radio theatre could be possible. The airwaves cover only a housing space. That is enough. I have been organizing micro radio party. This is an attempt to change a space to a qualitatively different by a micro transmitter.” (Kogawa)

This ability to measure transmission strength in feet as opposed to miles is fundamental for Radio Here. Further, it is his schematic that I followed as the starting point for the Radio Here transmitters.

Ultra-red

audio action collaborative

Ultra-red are an “audio action collaborative” that was formed by two AIDS activists in 1994. Over the years, the group has expanded to include members from many disciplines and social movements. Ultra-red conducts “Militant Sound Investigations,” using ambient sound and field recording techniques as a tool for activism and change. The collective uses prompts that invite participants to complete the phrase “What is the sound of...?” This simple prompt “requires listening in order to elaborate on those concerns and demands.” (Ultra-red 10) Ultra-red releases their recordings and those of their “allies” through their internet-based record label “Public Record.” This archive of free downloadable sound files is a public library of sorts for the distribution of the groups’ work.

I am inspired by Ultra-red’s ideas on the politics of listening through their conceptualization of “sustained collective listening.” Their work is based on intersecting theories of sound and politics. Ultra-red references Pierre Schaeffer, the French sound theorist who expanded the binary conception of sound as hearing versus listening to a more complex realm of continuums. He explored mapping sounds along ranges from objective and subjective, and abstract and concrete in order to capture more nuances in the types of sounds we are exposed to. Ultra-red also references Paulo Freire’s education work for critical consciousness. By overlaying Freire’s theories of radical education over Schaeffer’s expanded conceptions of sound Ultra-red reinforce their politically-minded pursuit of “Militant Sound Investigation.”

“Every sound exists in time and space. And since time and space are the building blocks of human activity and struggle, sound is a venue where perception meets action. It is where the body politic encounters the material.” (Ultra-red 23)

Radio Here agrees with some of the theoretical grounding, techniques, and goals of Ultra-red’s work. The “Record the sound of something...” prompts of Radio Here are intended to provoke an active search for sounds, which leads to listening. I believe this is a distinction from Ultra-red’s “What is the sound of...?” prompts that are meant to provoke silence first in a search for a response.

Sound Maps

the Montréal Sound Map, and Radio Aporee

Sound maps collect sounds that are then mapped and situated geographically, tagged to an exact time and location. Discussions of sound mapping question the spatial relationship of sound as it interacts with private and public space. This interplay becomes obvious when using visual mapping tools to explore the aural environment. Sound mapping questions the interplay of specific sounds in specific times in specific places.

Montréal based sound artist Max Stein and sound artist and composer Julian Stein launched the Montréal Sound Map in 2008. (Montréal Sound Map) This web-based project allows users to upload sound clips and images to a Google map of Montréal. The creators desire for this project is that it “offers an interface for users to explore and listen to the city with a purposeful and special attention that is rarely given to the sounds of the environment.” (Duzounian 166)

One of the oldest and most extensive on-line sound collection archives is Radio Aporee, started by Udo Noll. Initially launched around 2000, the map component wasn’t added until 2006. Global in scope, Radio Aporee has collected thousands of recordings from all around the world. However, more than simply a place to explore sounds uploaded to a map, the Radio Aporee project considers itself a platform for exploring boundaries:

“in addition to aspects of collecting, archiving and sound-mapping, the radio aporee platform also invokes experiments at the boundaries of different media and public space. within this notion, radio means both a technology in transition and a narrative. it constitutes a field whose qualities are connectivity, contiguity and exchange. concepts of transmitter/ receiver and performer/ listener may become transparent and reversible.” (Radio Aporee ::: Maps - Info & Help)

While sharing some of the same conceptual grounding as sound-mapping, Radio Here re-situates the listening experience. Sounds collected in a specific time and place are layered onto a new listening context. Space and time are updated, so that visitors to Radio Here are experiencing a new, layered, exploratory, and participatory form of listening.

Theoretical Approach

French philosopher and critical theorist Jacques Rancière challenges that in order to support a politics of dissent “it becomes necessary to invent the scene upon which spoken words may be audible, in which objects may be visible, and individuals themselves may be recognized.” (Rancière and Panagia 116) His politics needed a diverse set of voices in order to work, but his diversity also presupposed a built-in conflict. For me, his words invoke a welcoming environment, and I am not the first to begin to imagine his words as a reference to a physical and habitable environment. I saw a glimpse of this environment expressed in “Available Light”, a performance developed collaboratively by the composer John Adams, the choreographer Lucinda Childs, and the architect Frank Gehry. The score, the movement, and the structure each became influence and influencer in the conversation of sound, movement, and space. But the stage of theater is an exclusive space, and intentionally creates an environment separating the viewer and the viewed.

What might an inclusive architecture look like? What type of space might be intentionally created to bring more individuals into a place of conversation on equal ground?

Donna Haraway shares her own version of Rancière’s challenge. With her ideas around situated knowledges she seeks “those ruled by partial sight and limited voice—not partiality for its own sake but, rather, for the sake of the connections and unexpected openings situated knowledges make possible. Situated knowledges are about communities, not about isolated individuals. The only way to find a larger vision is to be somewhere in particular.” (Haraway 590) With this line of thinking as a point of departure, how might we create spaces that invite the unseen and unheard into a conversation—a conversation where these new voices and presences share new points of view?

Haraway’s essay “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective” posits a theory of the body’s location as it relates to the acquisition of knowledge. Haraway defines objectivity as a personal embodied experience, in opposition to a disembodied holistic view from what she terms the “God-eye view”. Only through the communal sharing of personalized knowledge might we begin to build an objective knowledge. In particular, Haraway argues moving away from the singularity of scientific objectivity towards situated knowledges; “for politics and epistemologies of location, positioning, and situating, where partiality and not universality is the condition of being heard to make rational knowledge claims.” (Haraway 589) This is where it may be possible to move away from Rancière’s aforementioned politics of dissent, or conflict, and towards a politics of care. The geographer Victoria Lawson calls this idea an “ethics of care,” and she argues that care is intimately connected to geography, “thinking of space as actively and continually practiced social relations—where we make choices that matter and that connect us to the lives of others.” (Lawson 6)

The challenge here becomes one of creating a space that might force a separation of content, or knowledge, in order to prevent the “God-eye view.” Haraway describes her essay as ”an argument for situated and embodied knowledges and an argument against various forms of unlocatable, and so irresponsible, knowledge claims.” (Haraway 583) She questions “objectivity” and aims to redefine how an objective interpretation might occur through a communication of multiple, situated, points of view. This points towards a politics of care by creating an arena for sharing perspective. Deleuze and Guattari, in their theory of the rhizome, saw these multiple points of view as a desire for everything to connect to everything else. “Nothing is beautiful or loving or political aside from underground stems and aerial roots, adventitious growths and rhizomes.” (Deleuze et al. 15)

However, there is danger in the situationalization of knowledge. Peta Hinton disagrees with Donna Haraway in her essay “‘Situated Knowledges’ and New Materialism(s): Rethinking a Politics of Location.” Hinton sees that for Haraway “the political terrain is a process of differentiation, through which identities and subjectivities are continually emerging in relational configurations.” (Hinton 108) Hinton ultimately argues that Haraway’s position does not create an objective, situated knowledge. She contends that any “situation” is already colonized, and so any point of view has to overcome this bias. This is related directly to creating a feminist politics that might create a truly unique point of view rather than just being one of “otherness”. If we are to “consider the nature of subjectivity along the lines that Haraway’s argument suggests, then enunciation gives way to annunciation, the announcement or arrival of an identity via its other.” (Hinton 108) With this warning in mind, any built environment will have to encourage sharing without setting up conditions of comparison and knowledge based on opposition. I hope to address this issue in the execution of Radio Here by setting up a multi-phased process based on asynchronous participation while honoring the variety of perspectives that will be formed and shared.

Communication and the Politics of Listening

Jürgen Habermas’s public sphere theory has been problematized many times since its introduction in the early 1960s. In her book Listening Publics: The Politics and Experience of Listening in the Media Age, Kate Lacey understands the problematic aspects of his theoretical arguments, but uses Habermas’ view of the public in another way—to think about acoustic space. She posits that the auditory realm “sits somewhere between the physical and the virtual, just as the public sits somewhere between the real and the imaginary.” (Lacey 6) Just as the public refuses to be categorized and defined, so too sound refuses binaries of listening and hearing, active and passive, and public and private.

Lacey borrows the idea of the “sphere” from Habermas as well. For her, the sphere becomes an infinitely permeable space open for anyone to enter from any direction. I think about this in the context of any architecture striving to embrace openness. It must have the ability to define without confining. Lacey notes that sound “surrounds, and can be approached from any direction, whereas the visual field is fixed and has to be presented face-on.” (Lacey 5)

The audio environment created by terrestrial radio broadcasting fits these criteria, and the utilization of radio waves has architectural connotations. Despite its seeming ubiquity, radio is fundamentally a local infrastructure with a finite range of coverage. Antenna heights, power levels, and topography all contribute to the physical limitations of the dissemination of radio waves. In this way, all radio is local radio. What appears disconnected is actually physically situated and defined by the landscape. Being in range or out of range creates conditions shared with architecture, those of being inside or outside.

Further, it could be argued that “broadcasting” is in direct conflict with the idea of community and the idea of participation. As mentioned earlier, Brecht wrote about this inherent tension in using radio as a participatory technology, observing that “the radio is one-sided when it should be two sided. It is only a distribution apparatus, it merely dispenses.” (Brecht and Silberman 42) He very clearly understood the difference between distribution and communication and felt that radio could do so much more.

However, with so many outlets for personal expression available today, I wonder if it might be worth investigating the radiogenic quality of radio’s one-sided mode of delivery by using it as a tool for breaking apart the stages of communication. With Radio Here, I propose a mode in opposition to what Manuel Castells calls mass self-communication facilitated in this digital age.

“It is mass communication because it can potentially reach a global audience.... At the same time, it is self-communication because the production of the message is self-generated, the definition of the potential receiver(s) is self-directed, and the retrieval of specific messages or content from the World Wide Web and electronic communication networks is self-selected.” (Castells 55)

I am advocating for the value of separation of participatory modes of communication, those stages of message creation, distribution, and consumption. I suggest that listening is no less a mode of participation and that it is a mode necessitating exploration.

Other Thoughts

Radio Here creates a space for listening. It takes the actions of communication—talking, listening, and responding—and separates them in time and location. In this way, the project attempts to become what Marshal McLuhan has called an “anti-environment” (McLuhan). By creating a space that challenges the expected conventions of technological participation, the “anti-environment” can reveal the state of the exiting environment. I draw upon histories of the low power FM radio movement, radical architecture, and theories of “Situated Knowledges” and politics of listening. Through the execution of this project, I hope to make observations that explore a few big questions; what happens when we pay attention; what happens if radio disappears; what is to be learned by separating modes of communication or participation?

What happens when we pay attention?

This has been a long-time theme in my work. I have done previous projects asking people to pay attention to where they were. Radio Here asks a similar question of paying attention with a focus on sound. This is in opposition to the sounds that are so easily brought along with us through portable music devices and headphones.

What happens if radio access disappears?

Radio has frequently been at the heart of freedom of speech discussions. From the Golden Age of radio in the inter-war years to the relatively recent battles over low-power FM, private and public interests understand what is at stake. Access to the airwaves has proved to be the most accessible, and most cost-effective way to communicate from one to many. Around the world, radio is the point of entry for raising the standards of living for remote, rural communities. Projects like RootIO in Northern Uganda is one example of an initiative that provides equipment and training so that “stations can start to facilitate new economic opportunities, new opportunities for expression and deliberation, and provide information across, into, and out of the community they serve.” (“RootIO”)

Current FCC Chairman Ajit Pai “is on record as saying that we are obligated to help the profit margins of corporate broadcasters, and that social media has rendered the need for local media presence obsolete.” (Labbe-Renault)

Policy decisions continue to shape and direct our communities. Local access to television and radio is more than broadcasting the high school football team and letting teenagers play music over the radio. Media access is access to information. Former FCC Chairman William E. Kennard was a champion of community radio—the addition of the Low Power FM license happened under his tenure. He was well aware of the potentials and dangers of the regulatory powers of the FCC, giving a general warning that “even though it is almost an invisible government agency, it plays a vitally important role in how people live their day-to-day lives and how our democracy functions.” (McChesney)

Currently, all forms of media are going through regulatory restructuring in favor of the corporate interest. Low-Power FM and small community radio stations face many challenges moving forward. A movement in needed to create a case for community radio as an environmental justice issue. I believe that the key lies in re-conceptualizing radio space as a community space—a space where communities live, work, and play. It may not be immediately apparent, but if radio goes away, our communities lose access to an important resource.

What is to be learned by separating modes of communication and participation?

My project takes the communication model and separates its components into three distinct modes of participation. It will be interesting to observe the interactions that happen within each mode. With Radio Here, I hope to create a space that achieves what Cedric Price refers to in his short article “A for Architecture”: “A is that which through self-conscious and unnatural means of distortion achieves socially beneficial conditions hitherto thought impossible.” (Price 113)

“[My work] seems to encapsulate my relationship with low-watt radio in how fragile and physical it is. Like a voice, it is ultimately individualistic and subject to so many kinds of suppression.”

Bibliography

Lacey, Kate, editor. Listening Publics: The Politics and Experience of Listening in the Media Age / Kate Lacey. Polity Press, 2013.

Lawson, Victoria. “Presidential Address: Geographies of Care and Responsibi.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 97, no. 1, Mar. 2007, pp. 1–11.

McChesney, Robert W. “Kennard, the Public & the FCC | The Nation.” The Nation, 14 May 2001, https://www.thenation.com/article/kennard-public-amp-fcc/.

McLuhan, Marshall. “The Invisible Environment: The Future of an Erosion.” Perspecta, vol. 11, 1967, p. 161. CrossRef, doi:10.2307/1566945.

Montréal Sound Map. http://www.montrealsoundmap.com/. Accessed 8 June 2018.

O’Brien, Kerry. “Listening as Activism: The ‘Sonic Meditations’ of Pauline Oliveros.” The New Yorker, Dec. 2016. www.newyorker.com, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/listening-as-activism-the-sonic-meditations-of-pauline-oliveros.

Oliveros, Pauline. Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice. iUniverse, 2005.

Opel, Andy. Micro Radio and the FCC: Media Activism and the Struggle over Broadcast Policy. Praeger, 2004.

Our Values | KDRT 95.7FM Davis. http://kdrt.org/about_kdrt/our_values. Accessed 4 Dec. 2017.

Price, Cedric. Re: CP. Edited by Hans Ulrich Obrist, Birkhauser, 2003.

Radio Aporee ::: Maps - Info & Help. https://aporee.org/maps/info/#about. Accessed 8 June 2018.

Rancière, Jacques, and Davide Panagia. “Dissenting Words: A Conversation with Jacques Rancière.” Diacritics, vol. 30, no. 2, 2000, pp. 113–26.

“RootIO.” RootIO Radio -- a Technology Platform for Low Cost, Hyperlocal Community Radio Stations, http://rootio.org/. Accessed 11 Mar. 2018.

Shannon, Claude Elwood, and Warren Weaver. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1949.

Soley, Lawrence C. Free Radio: Electronic Civil Disobedience. Westview Press, 1999.

Ultra-red. Ultra-Red Practice Sessions Workbook. 2014, http://welcometolace.org/lace/practice-sessions/ultra-red/.

Anguelovski, Isabelle. “New Directions in Urban Environmental Justice: Rebuilding Community, Addressing Trauma, and Remaking Place.” Journal of Planning Education and Research, vol. 33, no. 2, June 2013, pp. 160–75. CrossRef, doi:10.1177/0739456X13478019.

Benjamin, Walter, and Lecia Rosenthal. Radio Benjamin. Verso, 2014.

Brecht, Bertolt, and Marc Silberman. Brecht on Film and Radio. Methuen Publishing, 2000.

Castells, Manuel. Communication Power. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Chocano, Carina. “What Good Is ‘Community’ When Someone Else Makes All the Rules?” The New York Times, 17 Apr. 2018. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/17/magazine/what-good-is-community-when-someone-else-makes-all-the-rules.html.

Deleuze, Gilles, et al. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Continuum [u.a.], 1988.

Duzounian, Gascia. “Acoustic Mapping: Notes From the Interface.” The Acoustic City, Jovis, 2014, pp. 164–173.

Goodman, David. Radio’s Civic Ambition: American Broadcasting and Democracy in the 1930s. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, 1988, pp. 575–599. CrossRef, doi:10.2307/3178066.

Hinton, Peta. “‘Situated Knowledges’ and New Materialism(s): Rethinking a Politics of Location.” Women: A Cultural Review, vol. 25, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 99–113. CrossRef, doi:10.1080/09574042.2014.901104.

Kogawa, Tetsuo. “A Micro Radio Manifesto.” Tetsuo Kogawa’s Polymorphous Space on Micro Radio, Radio Transmission and Radio Art., http://anarchy.translocal.jp/radio/micro/index.html. Accessed 23 Apr. 2017.

Kubisch, Christina. Electrical Walks. http://www.christinakubisch.de/en/works/electrical_walks. Accessed 9 Feb. 2018.

—. Electromagnetic Induction. http://www.christinakubisch.de/en/works/installations/2. Accessed 12 Feb. 2018.

Labbe-Renault, Autumn. “Davis Media Access: One More Time: Why Local Media Matters.” The Davis Enterprise, 3 Nov. 2017, http://www.davisenterprise.com/local-news/davis-media-access-one-more-time-why-local-media-matters/.

“Listening is directing attention to what is heard, gathering meaning, interpreting and deciding on action.”